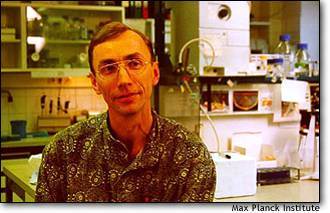

In his simply decorated office, he kicks off his clogs, folds his long legs under his angular body to perch on a sofa, and grins. But you'd never guess his heady position from his taste in clothes, which leans toward shorts and Hawaiian shirts. Paabo is director of the genetics department at the gleaming new Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany.

"He really is a visionary," says Mary-Claire King, a geneticist at the University of Washington. The first scientist to analyze segments of DNA from Neanderthal bones, Paabo now wants to re-create the entire DNA sequence of a Neanderthal and compare it with our own, looking for the reasons that one evolutionary experiment failed and the other succeeded.

This past summer, Paabo announced that he and his co-workers were going to take the next-and biggest-step, in their effort to resurrect the genome of the Neanderthal, our distant evolutionary cousin, who went extinct 30,000 years ago. He has been uncovering key genetic changes that helped transform our shambling, hirsute ancestors into the brainy bipeds we are today. He has helped show that human groups-southern Africans, Western Europeans, Native Americans-are closely related, despite superficial distinctions.

He's a leader of the worldwide quest to explore the past by analyzing human DNA. Paabo, 51, is still looking for artifacts, but in a very different place. "We went to the pyramids, to Karnak and the Valley of the Kings. "It was absolutely fascinating," he recalls. When he was 13, his mother, a food chemist in Stockholm, yielded to her son's most frequent request: to visit Egypt. After powerful North Sea storms uprooted trees, he begged his parents to take him to archaeological sites to look for potsherds and other artifacts. As a boy in Sweden, Svante Paabo read everything he could about ancient civilizations.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)